Fear of failure can hold back students, professionals, and anyone striving for growth. This guide explains why fear of failure happens, how it affects your life, and—most importantly—how to overcome it with proven strategies. Whether you want to advance your career, try something new, or simply feel less anxious about mistakes, this article is for you. You’ll find actionable advice, practical steps, and mindset shifts to help you move forward with confidence.

Key Definitions:

- Fear of failure refers to the intense worry or anxiety about making mistakes or not meeting expectations.

- Perfectionism is the belief that anything less than perfect is unacceptable.

- Growth mindset is the belief that abilities can be developed through effort and learning.

Key Takeaways

- Fear of failure is really fear of shame, judgment, and loss of status—not the event of failing itself. Most people can handle setbacks; what they struggle with is the imagined humiliation that comes with them.

- You don’t need to eliminate fear to take action. Changing your mindset, building new habits, and adjusting your environment allows you to act courageously even while feeling afraid.

- Small, low-stakes experiments—like trying a new hobby, sending one risky email, or journaling about past setbacks—are the fastest way to train your brain that failure is survivable.

- Persistent, debilitating fear that causes panic attacks, avoidance of basic tasks, or severe disruption to daily life may require professional support such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), a form of talk therapy that helps you identify and change negative thought patterns, or coaching.

- Understanding your motivation—whether you’re running from shame or moving toward growth—is a key pivot point that determines whether fear controls you or you control it.

The Fear of Failure Problem (and Why It Feels So Intense)

Picture this: someone you know—maybe even you—gets offered a promotion. More responsibility, more money, more visibility. And instead of excitement, there’s a knot in the stomach. What if I blow it? What if everyone realizes I’m not as competent as they thought?

The opportunity gets declined. Or the side business never launches. Or the application never gets submitted.

This is what fear of failure looks like in real life. It’s not weakness. It’s not laziness. It’s a deeply human response that affects most people at some point in their careers, studies, or personal lives.

Here’s what makes sense once you dig into the psychology: fear of failure often means fear of shame, embarrassment, or being “found out” as not good enough. The actual outcome—a missed deadline, a rejected proposal, a less-than-perfect presentation—is usually survivable. What feels unbearable is the anticipated humiliation, the loss of face, the confirmation of an inner suspicion that you’re somehow inadequate.

The High-Achiever’s Trap

This creates what researchers call the “high-achiever’s trap.” People with strong resumes, advanced degrees, and impressive track records can still feel like everything could collapse with one visible mistake. Success doesn’t inoculate you against this fear. In many cases, it amplifies it—because now there’s more to lose.

How Past Experiences Shape Fear

Your nervous system treats failure as danger because of past experiences, family messages, or workplace culture. A critical parent, a humiliating classroom moment, or a boss who punished mistakes harshly—these experiences train your brain to sound the alarm whenever similar situations arise. The fear response feels bigger than the facts because your body remembers what happened before.

The rest of this article will show you how to reframe what failure means, work with your emotions instead of fighting them, and build practical habits that gradually reduce the grip fear has on your decisions.

The Anxious Achiever’s Dilemma

Many ambitious people—students chasing competitive programs, professionals gunning for leadership roles, entrepreneurs building businesses—simultaneously crave growth and fear failing in public. They want the promotion, the launch, the recognition. But the thought of stumbling where others can see makes them hesitate, delay, or avoid entirely.

If this sounds familiar, understand something important: fear of failure doesn’t mean you lack intelligence, skill, or discipline. Often it coexists with a strong track record of success. The same drive that pushed you to achieve can also amplify the stakes of each new challenge.

Redefining Confidence

Here’s a reframe that changes everything: confidence isn’t “I feel no fear at all.” Confidence is “I trust that I’ll be okay even if this goes badly.” Most successful people feel afraid before big moments. The difference is whether that fear stops them or simply accompanies them.

Common patterns among anxious achievers include:

- Over-preparing obsessively for presentations (rewriting slides 47 times)

- Avoiding promotions or stretch assignments that increase visibility

- Saying no to dates, creative projects, or public speaking opportunities

- Endless planning with no execution because the first attempt might be imperfect

Motivation: Pride and Curiosity vs. Avoiding Criticism

Understanding your motivation is a key pivot point. Are you driven more by pride and curiosity—genuine interest in growth and mastery? Or are you driven primarily by avoiding criticism and shame—working hard mainly so no one can call you out? The answer shapes whether fear controls your choices or you control your fear.

Two Types of Motivation: Running From Shame vs. Moving Toward Growth

Imagine two colleagues, both working toward the same goal: launching a new initiative at work. On the surface, they look similar—putting in extra hours, researching thoroughly, preparing carefully.

But their internal experiences are completely different.

The first person is driven by fear of looking stupid. Every decision gets filtered through “what will people think if this fails?” They work hard, but the work feels heavy, anxious, obligatory. Even when things go well, relief lasts about five minutes before the worry about the next challenge kicks in.

The second person is driven by excitement and curiosity. They also feel nervous—that’s normal—but they’re more interested in what they’ll learn than in protecting their image. Mistakes are annoying, not catastrophic. They recover faster because setbacks don’t feel like evidence of fundamental inadequacy.

Research on Achievement Motivation

Research in achievement motivation confirms this distinction. Fear-based motivation works in the short term—it can push you to study harder or prepare more thoroughly. But it often leads to burnout, resentment, and never feeling “good enough.” Every completed task becomes a bullet dodged rather than a step forward.

Growth-based motivation builds resilience. When your worth isn’t riding on every single outcome, you can experiment, adjust, and keep going even when things don’t work the first time.

Fear-based motivation strengthens fear of failure by making your self worth dependent on every outcome. Growth-based motivation builds the ability to bounce back.

Later sections on values, small risks, and hobbies will help you gradually shift from fear-avoidant motivation to value-driven motivation. The goal isn’t to eliminate concern about outcomes—it’s to stop letting that concern run the show.

Validate Your Fear Instead of Fighting It

When fear of failure shows up, most people’s first instinct is to fight it. This is stupid. I shouldn’t be afraid. What’s wrong with me?

This invalidating self-talk actually makes things worse. It adds shame about being afraid on top of the original fear, teaching your brain that fear itself is dangerous and must be eliminated before you can act.

A more effective approach is emotional validation: noticing and accepting your fear as understandable without immediately trying to suppress or outrun it.

Here’s what that sounds like in practice:

“Of course I feel anxious before this presentation. It matters to me, and I’ve been criticized for mistakes before. This fear makes sense given my history.”

This isn’t resignation or wallowing. It’s acknowledgment. And counterintuitively, acknowledging fear often reduces its intensity faster than fighting it.

Try this practice:

When fear appears, name it out loud or in writing (“I’m feeling fear of failure right now”).

Acknowledge what it’s protecting (“This fear is trying to keep me from humiliation”).

Then choose one small action anyway (“I’m going to send this email even though I’m scared”).

Over weeks and months, this teaches your nervous system that fear is survivable. The intensity and duration of anxiety spikes gradually decrease. You stop needing to wait until you feel fully ready because you learn that readiness and fear can coexist.

Practice Failing Safely Through a Low-Stakes Hobby

One of the fastest ways to overcome fear of failure is to practice failing where it doesn’t count.

In the next seven days, pick a specific new hobby—something you’re genuinely interested in but have no existing skill in. Options might include:

- Beginner pottery or ceramics

- An improv comedy class

- Rock climbing at a local gym

- A language learning app (for a language you don’t speak)

- Sketching or watercolor painting

- A new sport or physical activity

The key is choosing activities where you are supposed to be bad at first. In these settings, mistakes are expected—even celebrated as part of the learning process.

This creates a “training ground” for your brain. You miss shots, fumble lines, make wrong notes, produce lopsided bowls—and nothing bad happens. Your income isn’t affected. Your reputation remains intact. Slowly, your brain starts to unlink mistakes from catastrophe.

When you mess up in your hobby, notice and stay with the physical symptoms: flushed face, tight chest, urge to quit. Practice supportive inner commentary instead of harsh criticism. “I’m learning. This is supposed to be hard at first.”

This playful exposure to failure often transfers back to work, study, and relationships. Taking risks starts to feel less paralyzing because your nervous system has fresh evidence that imperfection is survivable.

Clarify Your Values So Failure Doesn’t Define You

When your sense of self worth rides on every performance outcome, each potential failure becomes an existential threat. But when you have a clear sense of what actually matters to you—beyond any single result—individual setbacks lose their power to define you.

There’s a difference between “performing to look good” and “acting from what matters to me.” Clear values provide a more stable compass than perfect outcomes.

Exercise: Identify Your Core Values

- List 5–10 people you genuinely admire (alive, historical, or fictional).

- For each person, note the specific qualities you respect—courage, fairness, creativity, persistence, kindness, honesty.

- Look for patterns. These admired qualities point directly to your own core values.

- Now choose 1–2 of these values (e.g., learning, initiative, compassion) and before big decisions, ask yourself: Which choice moves me closer to this value, even if I might fail?

When success is redefined as “living my values” rather than “never failing,” setbacks feel like steps in a bigger, meaningful journey instead of final verdicts. A job interview that doesn’t lead to an offer becomes “I practiced showing up courageously” rather than “I’m a failure.”

Recognizing the Signs: How Fear of Failure Shows Up in Real Life

Fear of failure isn’t always obvious. It can hide behind busyness, overthinking, or statements like “I’m just being realistic” or “the timing isn’t right.” Here are some common signs to watch for:

Behavioral Signs

- Chronic procrastination—putting off important tasks until the last possible moment

- Giving up early when things get difficult

- Endless planning with no execution

- Declining promising opportunities because they feel too risky

- Only attempting tasks where success is virtually guaranteed

Emotional Signs

- Intense dread before evaluations, presentations, or deadlines

- Extreme fear or shame after minor mistakes

- Replaying conversations and projects from months or years ago

- Worry that spirals into worst possible outcome thinking

Physical Symptoms

- Racing heart and sweating before tests, meetings, or dates

- Tight chest and stomach discomfort

- Insomnia before important events

- Panic attacks in high-stakes situations

There’s a difference between everyday fear of failure and more severe patterns. When fear leads to avoiding basic tasks, social events, or any visible challenge—when it significantly disrupts daily life—this may indicate a condition sometimes called atychiphobia (an intense, persistent fear of failure), which can benefit from professional treatment.

Where Fear of Failure Comes From

Causes are usually layered and can include:

- Highly critical or perfectionistic upbringing: Parents who praised only top grades, compared children to higher-achieving siblings, or punished mistakes harshly can create lasting patterns. Children from these environments often internalize the message that love and approval are conditional on performance.

- Perfectionism and fixed mindset thinking: When you believe ability is fixed—“I’m either good at this or I’m not”—each setback feels like a permanent label rather than feedback on a learning curve.

- External pressures since around 2010: Social media creates constant comparison to curated highlight reels. Everyone else appears to be succeeding effortlessly while you struggle in private. Normal learning curves look like failure by comparison.

- Past failures: If you experienced failure in a high-stakes moment—failing a critical exam, losing a job publicly, being humiliated in front of peers—your brain may have encoded that experience as trauma, making similar situations trigger intense fear responses disproportionate to actual present-day risks.

Don’t blame yourself for having this fear. Understanding its roots is a way to choose more effective strategies going forward, not an excuse or a life sentence.

Perfectionism, Procrastination, and All-or-Nothing Thinking

There’s a common cycle that traps many people: wanting to do something perfectly, feeling overwhelmed by that unrealistic expectation, then putting it off until the last minute—or abandoning it entirely.

Perfectionism and procrastination often travel together because they serve the same function: protecting self worth from the threat of visible failure.

Here’s how it works:

- You set impossibly high standards (“This has to be perfect”)

- The gap between where you are and where you “should” be feels overwhelming

- You delay starting to avoid confronting that gap

- Last-minute work produces subpar results, confirming you’re “not good enough”

- The cycle repeats with higher anxiety next time

Procrastination is a short-term anxiety relief strategy that backfires. It provides temporary escape from fear but increases long-term stress and reinforces the belief “I can’t handle this.”

Breaking the cycle:

| Instead of… | Try… |

|---|---|

| “Launch a perfect business by June” | “Test one small offer with 5 customers by end of month” |

| “Write a flawless report” | “Complete a rough draft, then improve one section at a time” |

| “Give a presentation with no mistakes” | “Prepare well and accept that minor imperfections are normal” |

Practicing “good enough” outputs—like sending an 80% polished email or submitting a draft that isn’t perfect—gradually weakens the perfectionism-procrastination loop. Each time nothing catastrophic happens, your brain updates its predictions.

Practical Strategies to Overcome Fear of Failure

This is the core “how-to” section. The strategies below are specific enough to start implementing this week—in work, school, or personal projects.

Pick 1–2 strategies to try immediately. Don’t wait until you feel fully ready or fearless. That day won’t come without action first.

The most effective approach combines:

- Mindset shifts (changing beliefs about what failure means)

- Behavior changes (taking small actions despite fear)

- Emotional skills (tolerating discomfort without running from it)

Some strategies are inward-focused (thinking, journaling). Others are outward-focused (risk-taking, conversations). Mix according to your preference and situation.

Progress is usually gradual. You measure it in slightly quicker recovery from setbacks and slightly bolder choices over months—not overnight transformation.

Redefine What “Failure” Means for You

Many people operate with vague, harsh definitions of failure—“not being the best,” “making any mistake,” “not exceeding expectations.” These definitions guarantee constant disappointment because they’re impossible to meet consistently.

Exercise: Define your terms

Pick a common scenario (job interview, exam, product launch, important conversation) and define three outcomes in specific, realistic terms:

| Outcome Level | Specific Definition |

|---|---|

| Success | Receive offer / Pass with B or above / Get 10 paying customers |

| Okay | Perform competently, don’t receive offer but get good feedback / Pass but not stellar / Get 5 customers and useful insights |

| Failure | Arrive unprepared, visibly struggle, make major factual errors / Don’t pass despite reasonable preparation / Zero interest after genuine effort |

Notice how this shifts the threshold. An interview that doesn’t lead to an offer isn’t necessarily a failure—it might be “okay” if you showed up prepared and performed competently.

Include process metrics alongside outcome metrics:

- Did I show up prepared?

- Did I ask good questions?

- Did I submit on time?

- Did I give sustained effort?

Then reframe your language. Instead of “I failed,” try “This attempt didn’t work yet—what can I adjust next time?” This turns failure into information about strategy, not your worth as a person.

Take Tiny, Calculated Risks Regularly

Fear shrinks when you repeatedly survive small, controlled risks. Not massive, bet-the-farm gambles—just slightly scary actions that stretch your comfort zone.

Create a weekly “risk list” with 3 small actions:

- Apply to one stretch role or opportunity

- Post a piece of writing or share an idea publicly

- Ask for feedback on a draft from someone whose opinion matters

- Start a conversation with someone who intimidates you slightly

- Volunteer for a task that’s slightly outside your expertise

Choose risks that are emotionally noticeable but not overwhelming. You want to feel discomfort, not panic. The goal is accumulating evidence that you can handle things going wrong.

Track results in a simple log:

| Date | Action Taken | What Happened | What I Learned |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12/15 | Asked manager for feedback on project | Got constructive criticism about timeline | My work isn’t as bad as I feared; I can improve planning |

| 12/18 | Submitted article to publication | Rejected | Rejection was disappointing but not devastating; will revise and try elsewhere |

Over 2–3 months, this habit rewires your sense of what you can handle—often more powerfully than reading advice alone.

Use Better Self-Talk Before, During, and After Setbacks

What you say to yourself in key moments matters as much as the external outcome. Negative self talk can turn a minor setback into a spiral of shame; supportive self-talk can turn the same setback into a learning opportunity.

Examples of harsh vs. helpful internal dialogue:

| Harsh | Helpful |

|---|---|

| “If I mess this up, everyone will know I’m a fraud” | “This is challenging, but I’ve handled hard things before” |

| “I always fail at things like this” | “I’ve struggled with similar tasks, and I’ve also improved over time” |

| “I can’t believe I said that—I’m such an idiot” | “That wasn’t my best moment, but one comment doesn’t define me” |

Create a self-talk script for stressful events. Before a presentation, exam, or difficult conversation, rehearse statements like:

- “I’ve prepared well. I can handle what comes.”

- “Even if this doesn’t go perfectly, I’ll learn something.”

- “Feeling nervous is normal—it means I care.”

After a setback, use a debrief template:

- What actually happened? (Facts, not interpretations)

- What was in my control?

- What can I do differently next time?

- What did I do well despite the outcome?

Consistent, kinder self-talk reduces the shame spike after failures, making it easier to try again instead of withdrawing into self sabotage or avoidance.

Talk to Someone You Trust About Your Fears

Fear of failure often thrives in secrecy and isolation. When worries live only in your head, they go unchallenged and tend to grow more extreme.

How to get support:

- Pick a specific person—friend, mentor, manager, therapist, or executive coach—and share a concrete situation you’re avoiding because you feel afraid of failing.

- Be specific about what kind of support you need:

- Emotional support: “I just need you to listen and understand why this feels hard”

- Practical input: “What’s a smaller first step I might be missing?”

- Reality check: “Am I catastrophizing, or is this risk as big as it feels?”

Hearing alternative perspectives can recalibrate what feels “unrecoverable.” A family member or mentor might remind you of past failures you’ve already bounced back from. They might share their own negative experiences with failure, normalizing imperfection.

If fear is severe or connected to trauma, or if it blocks basic life tasks, professional help is especially valuable. A mental health professional trained in approaches like CBT (cognitive-behavioral therapy)—a structured, evidence-based form of talk therapy that helps you identify and change negative thought patterns—or exposure therapy (gradually confronting feared situations in a controlled way) can help you work through deeper patterns safely.

Remember the Cost of Not Trying

When fear spikes, your brain focuses intensely on potential negative consequences of action. But avoiding failure also means avoiding potential growth, income, relationships, and satisfaction.

Reflection exercise:

- Imagine yourself 5 or 10 years from now. Write briefly about the regret you might feel if you never try the things that scare you today.

- Then list specific “costs of inaction”:

- Stalled career progression because you never applied for challenging projects

- Missed creative expression because you never shared your work

- Ongoing resentment from always choosing the safer path

- Professional growth opportunities that went to people who were willing to fail

Use this list when fear spikes. Balance the brain’s focus on potential loss from failing with the real loss from never stepping forward.

Research consistently shows that most people regret chances not taken more than attempts that didn’t work out—especially when they learned something important in the process. The pain of “I never tried” tends to outlast the pain of “It didn’t work.”

Overcoming Fear of Failure at Work

Failure at work—botched presentations, missed promotions, disappointed clients—feels uniquely threatening. Money, reputation, and professional identity are all on the line.

But here’s what every experienced professional knows: every workplace experiences failed ideas and missed targets. Startups fail to find product-market fit. Large corporations abandon initiatives. Teams miss deadlines. The difference isn’t whether failure occurs—it’s whether organizations and individuals learn from it.

Adopt a “Learning Project” Mindset

Each task at work is a test of a hypothesis, not a final exam on your own performance and worth. You’re gathering data, not proving your value as a human.

Start with smaller experiments:

- Pilot a new idea with a small group before rolling it out broadly

- Request feedback early in a project, when course corrections are still easy

- Volunteer for a slightly scary but manageable task outside your usual scope

- Treat constructive criticism as useful information rather than personal attack

A healthier relationship with failure at work leads to better innovation (because you’re willing to try things that might not work), stronger relationships with managers (because you’re honest about challenges), and career growth over time (because you take on opportunities others avoid).

Mine Past Failures for Hidden Benefits

Many job-related failures—lost clients, missed deadlines, unsuccessful job interviews—contain usable data once emotions cool down.

Exercise:

Pick one work “failure” from the past few years. Maybe it was a failed first attempt at something new, or maybe failure occurred in a more dramatic way. Then list at least three concrete benefits or lessons that came from it:

| Past Failure | Benefits/Lessons |

|---|---|

| Lost a major client | Forced us to diversify; improved our onboarding process; learned to set clearer expectations upfront |

| Didn’t get the promotion | Identified skill gaps I needed to address; motivated me to seek mentorship; realized that role wasn’t right for me anyway |

| Project delivered late | Created better timeline estimation process; learned to flag risks earlier; strengthened team communication |

Identify skills gained: improved communication, resilience under pressure, more realistic time estimates, stronger systems.

Turn insights into forward-looking actions. If you learned that you need earlier stakeholder updates, build that into your project templates. If you learned you underestimate timelines, add buffer to future estimates.

This process reframes past failures as assets rather than permanent scars—and lowers anxiety about future risks.

View Big Tasks as Challenges, Not Threats

Your brain can frame the same situation as either a threat (“This must go perfectly or I’m doomed”) or a challenge (“This is hard but an opportunity to grow”). The frame you choose affects your physiology, your focus, and your performance.

Pre-task ritual:

- Recall 2–3 past successes or difficult things you handled well.

- Describe the upcoming task in neutral or positive terms (“chance to test my ideas” instead of “moment of truth”).

- Remind yourself that you’ve prepared and can handle whatever happens.

Combine this mindset work with realistic preparation—good slides, rehearsals, contingency plans. Confidence works best when it’s based on real readiness, not wishful thinking.

Over time, your brain starts to associate big tasks with possibility and growth rather than automatic danger. The fear response doesn’t disappear, but it no longer runs the show.

Practice Self-Compassion After Mistakes

Self compassion means treating yourself like you would treat a capable, well-meaning colleague who just made the same mistake. Not harsh criticism. Not letting yourself off the hook. Just basic decency and perspective.

Three-step response to failure:

- Acknowledge the pain: “This really hurts. I’m disappointed.”

- Normalize it: “Everyone slips up sometimes. This doesn’t make me uniquely flawed.”

- Choose a kind next step: “What would help me bounce back? What action can I take?”

Concrete self-care ideas for work stress:

- Take a short walk before addressing the problem

- Debrief with a mentor or trusted colleague

- Schedule specific time to fix the issue rather than ruminating indefinitely

- Remind yourself of your broader track record

Self-compassion isn’t weakness or excuse-making. It’s creating the emotional safety needed to take responsibility and improve. Research shows that workers who respond to their own mistakes with compassion recover faster and perform better on subsequent tasks than those who berate themselves.

When to Seek Extra Support

While many fears of failure can be managed with self-help strategies, some patterns are intense enough to warrant professional support.

Red Flags That Suggest Professional Help

- Frequent panic attacks before performance situations

- Avoiding work or school entirely due to fear

- Turning down nearly every new opportunity

- Extreme fear that persists despite repeated efforts to change

- Fear connected to traumatic past experiences

- Significant impact on relationships, health, or well being

Evidence-based approaches that help include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): Identifies and restructures the thought patterns that fuel fear.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Teaches psychological flexibility and values-based action. ACT helps you accept difficult emotions and commit to actions aligned with your values, even in the presence of fear.

- Exposure therapy: Gradually confronts feared situations in a controlled way.

- Coaching: Focuses specifically on performance anxiety and professional development.

A mental health professional can help unpack deeper roots—chronic criticism, public humiliation, specific phobia patterns—and design graded exposure plans safely.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Reaching out early—whether to a therapist, counselor, or executive coach—can prevent fear of failure from hardening into long-term avoidance patterns. Many successful people work with professionals not because they’re broken, but because they want to overcome obstacles more efficiently.

FAQ

Is fear of failure always a bad thing?

No. A moderate fear of failure can be a net positive—it signals that something matters to you and motivates preparation. It becomes problematic when it leads to chronic avoidance, paralysis, or intense shame that stops you from pursuing meaningful goals. The goal isn’t to eliminate fear entirely, but to change your relationship with it so you can act despite feeling afraid.

How long does it take to overcome fear of failure?

It varies significantly. With consistent practice—small risks, reframing thoughts, reflection—many people notice changes within a few weeks: quicker recovery from setbacks, slightly bolder choices. More substantial shifts typically take 3–6 months of sustained effort. Deeply rooted fears tied to trauma or long-term patterns may take longer and often benefit from working with a mental health professional.

Can I overcome fear of failure without therapy?

Many people reduce everyday fear of failure using self-help tools like journaling, graded exposure to small risks, positive thinking practices, and mindset work. However, if your fear causes severe distress, affects your health or relationships, includes frequent panic attacks, or stops you from basic responsibilities, therapy or counseling is strongly recommended. There’s no shame in getting help—it’s often the most efficient path forward.

What if my environment punishes failure harshly?

In workplaces or families where mistakes are heavily criticized, start with low-stakes experiments you control—side projects, learning outside of work, hobbies where you lack confidence but can practice. Over time, you may also need to advocate for healthier norms, set boundaries, or even change environments to support sustainable growth. Sometimes the bravest thing is recognizing that an environment is incompatible with your well being.

How can I help a child or teenager with fear of failure?

Focus on praising effort, strategies, and persistence rather than only outcomes or grades. Normalize mistakes by sharing your own and discussing what you learned. Encourage them to try new activities where it’s safe to be a beginner, and avoid harsh criticism that links their worth to performance. When they encounter roadblocks, help them problem-solve rather than rescue them—building the belief that they can overcome challenges themselves.

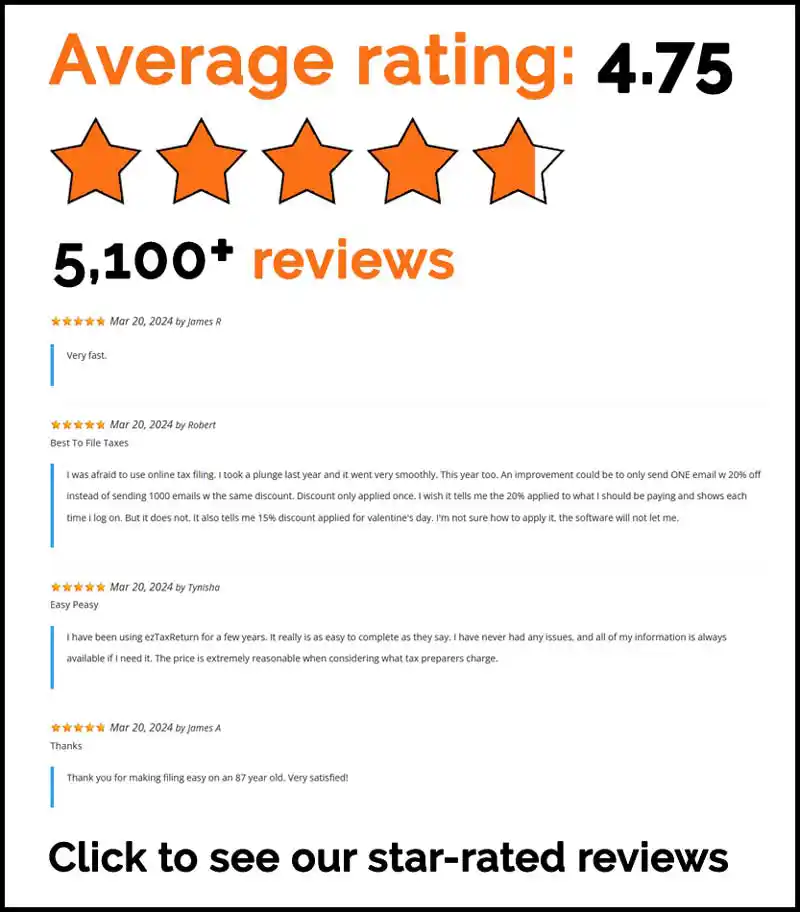

Big tasks don’t have to feel overwhelming. When you’re ready, ezTaxReturn makes doing your taxes simpler, step by step—so you can move forward with confidence.

The articles and content published on this blog are provided for informational purposes only. The information presented is not intended to be, and should not be taken as legal, financial, or professional advice. Readers are advised to seek appropriate professional guidance and conduct their own due diligence before making any decisions based on the information provided.